Designer Maximiliaan Frederik (Max) Gunning, naval engineer 1895 †1972

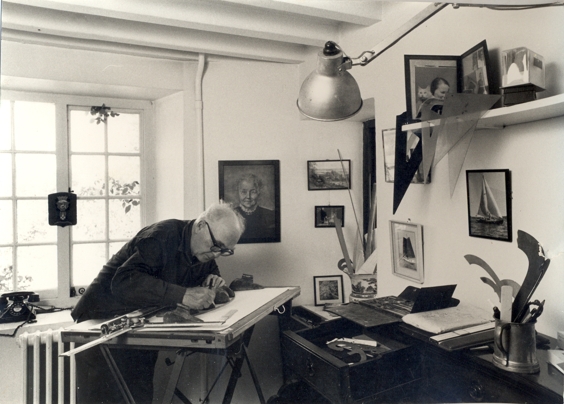

Retired Max Guning in his workroom in Petersfield / England

Retired Max Guning in his workroom in Petersfield / EnglandPhoto archive Anne Marie Scheltema

Max Gunning was born on October 9, 1895 in Zwolle. He was the eight and youngest son of professor Dr. Jan Gunning and Cecilia van Eeghen. He stems from an upper class family with an academic background. Until his graduation as naval engineer, in 1922, he lived in Delft and after that, because of his work for the Koninklijke Marine (Royal Navy), in The Hague, Hellevoetsluis and Vlissingen. He succeeded in his career and became manager (1935-1940) and permanent consultant (1945-1960) of the design consortium N.V Nederlandse Verenigde Scheepsbouwbureaux (Dutch United Shipbuilding Agencies PLC) (NEVESBU) in the Hague, where work was done for the four biggest shipyards in the Netherlands. Basically NEVESBU was his brainchild.

In 1940, when the war broke out, he decided to flee to England via Portugal, in all probability with help from the Navy. Max Gunning was appointed Head Engineer in the Dutch Ministry of Naval Affairs which was stationed in London. He was responsable for the completion and repair of warships like HNLMS van Heemskerk and Isaac Sweers, hurriedly transported across to England. In 1942, in the middle of the war, he conceived the brilliant idea for a three-cylindre cargo submarine with a bigger carrying capacity. This made it possible to transport goods to the allied forces in Africa at a smaller risk than by way of the famous Malta- convoys. But the British expected to be able to beat the German general Rommel very soon and dropped the plan, also because the estimated building time was at least one year.

For many years Max Gunning was in the frontrank of the Koninklijke Marine (Royal Navy) regarding the designing of warships. He was the man who devised the post-war new model convential submarine of the three-cylindre type, with an unprecedented maximum diving depth of 350 meters. Between 1954 and 1966 four submarines of this so called Dolphin class were built. Only the submarine HNLMS Tonijn has been preserved. The Tonijn is kept on shore in the Naval Museum at Den Helder, where it can still be seen.

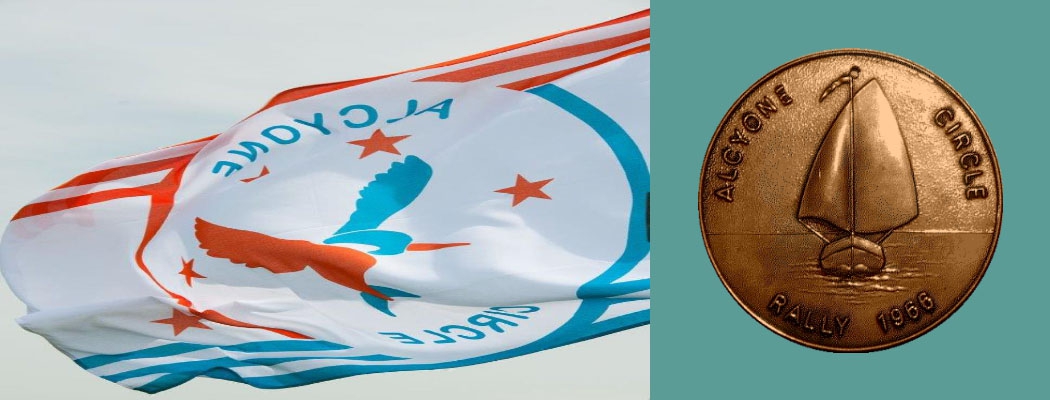

In 1946 Max Gunning remarried. With his new wife Julie Scheltema he settled down in Petersfield (Hamsphire, England) as consulting engineer and he lived there till he died in 1972. In the period after the war Max Gunning, in addition to his actual job, started occupying himself seriously with yacht design. In 1947 he had the steel-hulled sailing-yacht Alcyone I built – for himself, but also as a prototype- on the Valentijn yard at Langeraar. This yacht formed the basis of the five Gunning classes: AlcyoneI (1948), Alcyone II (1957), Expanded Alcyone II ( 1959), Cormorant (1962), and the Alcyone III (drawings on tracing paper 1968), which was never built however.

The centre-board yachts by Gunning are famous for their solid, basically simple, very practical and functional architecture. This is mostly due to his professional background. Also the post-war reconstruction period had its influence. It was the era of functional designs and fast, efficient and relatively cheap constructions. Max Gunning can, indeed, be seen as a Rational Modernist.

He had the British upper class (by nature averse to excess, luxury and ornamentation) on his side and they were the first to have Alcyones built on the Valentijn yard. Later they made fantastic sea voyages and ocean voyages with these yachts.

In the period between 1946 and 1967 Gunning wrote articles about some of his beloved designs in Yachting Monthly. After his death on February 13, 1972, Sir Percy Wyn-Harris concluded this series and wrote an impressive obituary in the May edition of 1972 of Britain’s best loved cruising magazine. The passionate professional Max Gunning, with his creative mind and his talent for construction can, on the basis of his extensive maritime design inheritance, indeed be considered an important en complete designer. In Holland though, Gunning was never given the attention and recognition he actually deserved according to his merits and his design for a scientific and seaworthy flat-botommed yacht. The British and Americans on the other hand, understood his designs and valued them.